“Am I earth? Or am I sulfur?” I overheard this while at a dinner party.

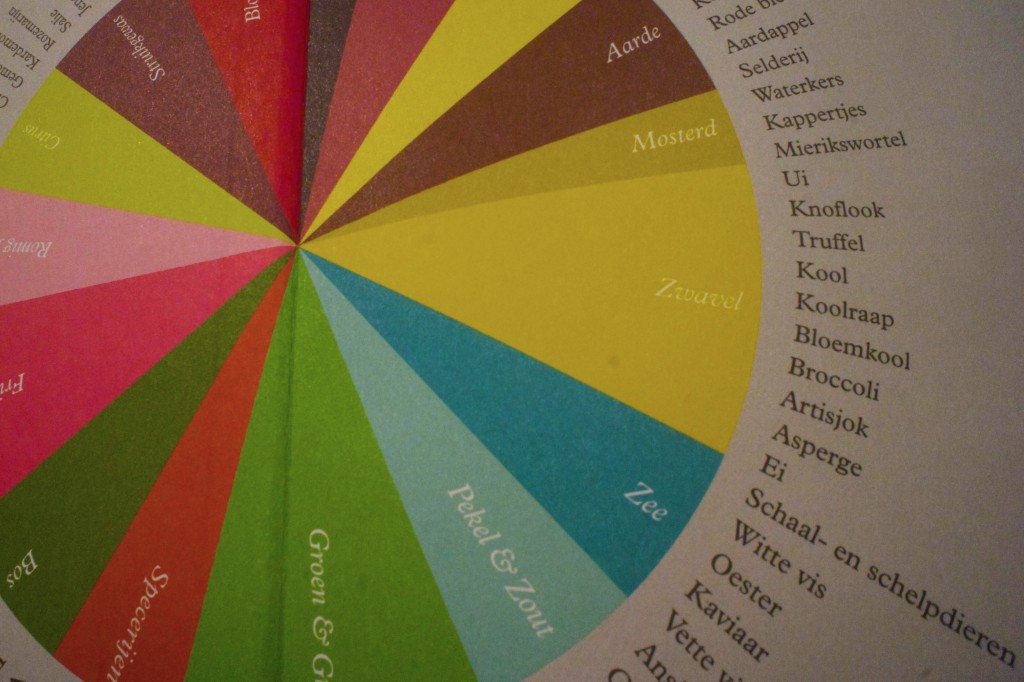

People were laughing. I didn’t get what they were talking about. A friend held a book in her outstretched arms, turning it around and around like a steering wheel, while the others pointed at various parts of a pie-chart-like circle on the front endpaper of the book.

“I’m definitely citrus,” one person said. “Or fresh fruit,” another replied. I started to recognize the categories. Over the past few weeks, this book had become both essential to my cooking and my favorite bedtime literature.

The categories weren’t psychoanalytical. They were food. My dinner companions were using the wheel of Niki Segnit’s Flavour Thesaurus as a mold for their personalities. But it didn’t work; they decided their personalities couldn’t be classified by labels on the wheel. Apparently, our ids, egos, and beings can’t be defined in terms of watermelon, butternut squash, or cumin. The book wasn’t meant for that in the first place, but the conversation was too heated for anyone to notice my interjections. I couldn’t convince them of the book’s non-psychological brilliancy, and it was tossed aside. I figured it was time to go home.

At the time, the thesaurus was my most inspiring cheffing resource. For years, my walls were paneled with books and magazines that told me what to cook and how to cook it. Over time, the stacks started feeling like the walls of prison, limiting my creativity rather than feeding it. But Segnit set me free. She re-introduced me to ingredients and introduced ingredients to me. She gave me the tools to dig deeper into recipes, making reading cookbooks an active and involved practice, rather than a passive one. Being able to engage with my books, they became sources I could learn from again, and I learned to love them anew.

In her book, Segnit describes foods through their flavors, categorizes them accordingly, and presents them as meaningful duos, pairing raspberry with basil, beetroot with horseradish, and coriander with coffee. She gives you an idea rather than a recipe. Not an order, but a gentle push in a direction. Segnit’s book opened up my cooking to experimentation: spicing up a bland eggplant risotto with nutmeg, or replacing lemon and parsley with orange and coriander in a fish recipe.

This also inevitably means that Segnit opened up my cooking to the occurrence of failure. Following recipes is like reading a language. At one point you can. You know you won’t fail. But going off the recipe means things won’t always work out. And this failure is liberating. It teaches you something, namely that (and maybe even why) what you thought would be great isn’t. It’s scary too. You can no longer blame the recipe. You, your experiment, and your interpretation are at “fault”. This is why I don’t fail enough in the kitchen yet, but I’m slowly learning to embrace it. Segnit teaches me how to take baby steps.

Having spent years focusing on Jamie’s Italy and the seminal Silver Spoon, I thought Italian food was the absolute, unsurpassable summum of cuisines. And the food is great, although a great deal less delicious if you’re stuck using Dutch tomatoes. But I discovered there are so many more cuisines to explore. Californian and Australian are both fantastic fusion kitchens. Or the hearty German, Flemish and Austrian dishes that comfort me during cold winters. And my newest fad: Lebanese. You know you’ve entered unknown territory when you’re buying produce with Google Images, because the name written in the list of ingredients means absolutely nothing to you.

No longer looking for recipes, but for combinations of ingredients, the Flavour Thesaurus has led me to the more unfamiliar corners of my bookshelves. By focusing on pure ingredients rather than geographical kitchens, Segnit changed the way I navigate recipes. I love cooking Asian food, mainly because I love ginger. Shifting my focus from Asian to ginger, however, I learned about Dean & Deluca’s lovely but untraditional tomato and ginger pasta sauce. Or take horseradish: I love horseradish, but I didn’t know what to do with it besides combining it with roast beef. When I was in Vienna, I discovered that it’s a staple in the Austrian kitchen. So I started cooking Austrian food, which I probably would’ve never done otherwise. The Flavour Thesaurus is like a culinary Lonely Planet: it gets you off the beaten track, but makes sure you don’t get lost.

Three combinations and ideas to get started

Coriander and coffee

Segnit advises to start with 1 teaspoon of coriander seeds on 6 tablespoons of coffee beans and go from there.

Grind them together? Or grind separately and brew all together? She doesn’t say. This is where the journey begins. But I hardly drink coffee and don’t have a coffee grinder. Who wants to give this a try?

Raspberry and basil

Donna Hay makes a mean Moscow Mule. Mix about half/half of vodka and ginger beer, stir in lime juice syrup to taste. Serve with raspberry ice cubes and basil leaves.

Beetroot and horseradish

Austrian cuisine and I love horseradish. Tafelspitz (cooked beef), a national dish, comes with many, many sides.

My favorite is a salad with beetroot, apple and horseradish. Grate cooked beetroots, apple, and horseradish. Mix in some roasted cumin seeds and vinegar. Have some leftover beetroots from yesterday’s dinner? You think roasting will add an extra dimension of flavour? You like your food spicy? Go with your gut.

And yes, there are recipes in there too. For the lazy days.